Hanif Abdurraqib

Written By: Lauren Sega | Photos By: Ben Leeson & Abigail Tabler

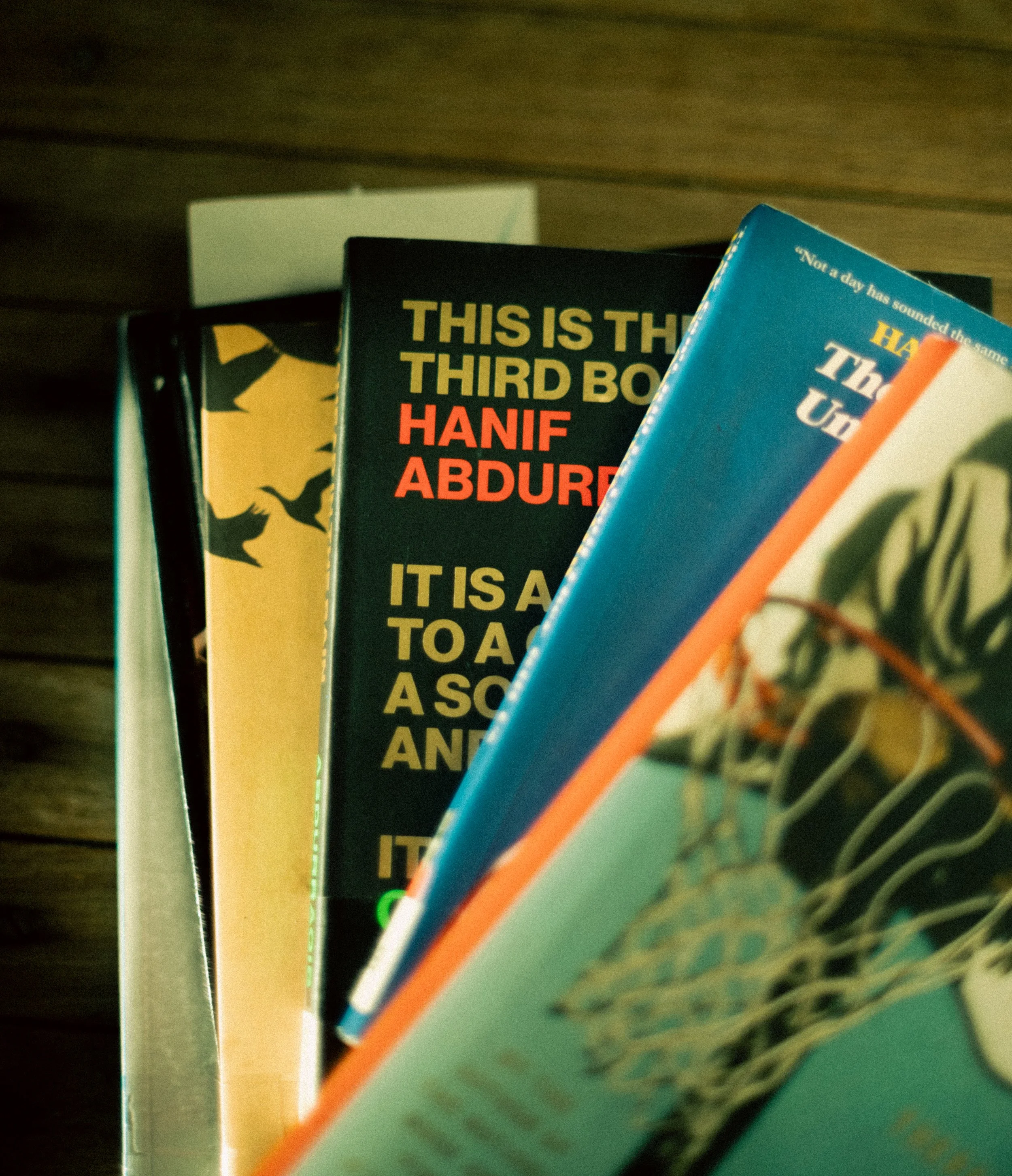

In a too-brief conversation with Columbus treasure, acclaimed author and poet, and unabashed romantic, Hanif Abdurraqib, I got just the trimmings from a length of insight he possesses on growing up, growing old, leaving and finding home. A methodical man in his routines and rituals, Hanif categorizes and organizes his interests in a pained effort to never lose track of the things that grip him. In an era fixated on the next dopamine hit, Hanif slows it all down, demonstrating an interrogation of self and society that embraces the flaws, the features, and the frustrating unknowns.

Tell me about your relationship with Columbus.

I grew up on the East Side and to be back [there] is refreshing and renewing, particularly in Bronzeville. It’s its own contained village.

So escaping your hometown was never part your plan?

I think I run into people all over from Columbus who have made a path elsewhere, but I never felt that impulse to leave. I've been unhoused here. I've been in the hospitals here when I did not necessarily want to be alive. I've had a lot of lives here that I think would send a lot of people wanting to, perhaps, remove themselves from this place and its history and the way that history has been afflicted upon them.

Which I get. I mean, I truly understand that, because it could feel like confrontation, right? For me, this just never just felt like confrontation. I want to keep growing into the self I am now while honoring those selves that I had to endure and survive to get to the self I am now. If I reckon with the geography and how it's had an impact upon me, I could perhaps be a much more satisfied and more honest version of myself.

“I want to keep growing into the self I am now while honoring those selves that I had to endure and survive to get to the self I am now.”

How have you seen Columbus’ self change since your childhood?

Columbus has changed infrastructurally, but none of it speaks to the city itself, its people. I worry about people being left behind in all the large infrastructural changes. I grew up in a neighborhood that is largely similar to what it was. The times and ways the Black community in the city used to gather, look upon each other, have these kinds of experiences that were joyful – and we’re not totally devoid of that, of course – but the frequency with which that happened when I was young felt so immense, particularly in the summer. And I feel like what gentrification does is, in one way, it disjoints those communities, moves people around, scatters those communities.

Does your latest book, There’s Always This Year, speak to Columbus specifically?

I mean, it's distinctly my most Ohio book. It’s very much rooted in Ohio and Columbus, but I don't know if it's only speaking to those folks. I think it's speaking to a wide range of various people across various spectrums, largely – or hopefully – people who have relationships with their parents that are crystallizing for them as they age. People who think about dying sometimes. People who play basketball, but not exclusively. People who watch basketball, but not exclusively. People who think about time and the passage of it. There's no one answer, I think, and that's the way I think that most of my writing attempts to be.

“I feel like what gentrification does is, in one way, it disjoints those communities, moves people around, scatters those communities.”

On rituals and regimens

I will follow my dreams wherever they take me

I will stand upon the mountain and look down upon the seashores

But I'll always remember

The family table

If I don't ever go there anymore

-Family Table, Bill Withers

What’s your process in finding new music?

I make playlists weekly of new songs that move me, and I share it with people, but it’s a lot for myself to keep track. I really love the Chelsea Wolfe album that came out a few weeks ago. That’s my favorite album of the year. My favorite new band this year is a band called Lazy Sunday in Portland, and they released an album called Another Summer that I just adore, and I haven’t been able to stop listening to. I really love the new Laura Jane Grace record and the new serpentwithfeet album.

How do you keep track of it all?

I’m very organized when it comes to music. I have my Spotify broken into segments. I have folders on my computer and a spread sheet of what I’m listening to.

When did you start this project?

The bones of it, I think, started when I was young. I’ve always been interested in the cataloguing of things I’m excited about. You know, part of this is that I grew up alone, and I also grew up really poor.

I said I grew up alone – not in a bad way. I’m the youngest of four, and I grew up in a very loving house, but, when you’re the youngest of four, everyone has their own lives, and you have to figure out your own life, largely on your own, and for me that meant recording a lot of songs I loved off the radio and recording music videos I loved on VHS tapes in the VCR.

Now, this listening practice in a tangible, material way, probably started around 2018. Streaming encourages us to believe we have everything at our fingertips. It’s easier for me to say, I discovered this band this week and I love this band, and I can access their album much easier than if I were discovering a band in, say, 1996. Another thing that streaming does is require people to have short attention spans around what they’re hearing, and I really want to love and savor things for a long time. I like remembering what especially moved me so that in September I can still listen to that Lazy Sunday record like it just came out. I don’t want to leave things behind when I feel affection towards them. The kind of instantaneous nature of how we receive and consume everything kind of presents this thing to us where it feels like we can love something temporarily and then we can leave it behind and go to the next thing and the next thing and the next thing.

On There’s Always This Year

You ask me what I think about this

Is there even a reason for it?

I don't have answers, no one does

I've been finding comfort in that

There's only love

There's only moving through and trying your best

Sometimes it's not enough

Who gives a fuck

All of this will end

Don't forget

All of this will end

-All Of This Will End, Indigo De Souza

When did the seed for There’s Always This Year become planted?

I think I wanted to write the book for a very long time but didn’t have the capability to do it. All of writing is, we dream this kind of limitless concept for something, or we dream in a limitless form. But our actual abilities have limits, and so much of the process is what kind of gap you’re okay with – the gap between your limitations and your dream. For me, that gap was just too big in 2018, 2019. This was the kind of book that I had to write other books to know how to write it, and that’s a part of the process too. The seeds of this came to be in 2018, but I certainly wasn’t ready to write it until 2021.

How do you set out on a task to write about LeBron James and basketball and create a thread through themes like love and loss and coming of age and coming home?

I think it’s all a result of me being eager to be wrong about what I’m thinking I’m pursuing. I think I approach it all with a lack of commitment. Sure, when I first set out on this book I thought I was going to be writing some kind of ode to LeBron James and place and time, but I also knew that in the process of writing, I would be confronted with the reality that I’m actually wrong about what I’m after, and you have to be open to that.

No one’s ever pursuing one thing. No piece of writing is about one thing. Because it is actually encompassing this project, this garden that we all kind of walk upon and choose to work within where we are aware – distinctly aware – that we’re not just writing about the one thing. And I just choose to not resist that.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity. Original interview recorded April 2024.

Published June 2025